Doclea (Montenegro) in Late Antiquity: some remarks from the Italian-Montenegrin bilateral projects

Carla SfameniCNR, Istituto di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale (I)

Lucia AlbertiCNR, Istituto di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale (I)

Francesca ColosiCNR, Istituto di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale (I)

Tatjana KoprivicaUniversity of Montenegro, Historical Institute (MNE)

Olga Pelcer-VujačićUniversity of Montenegro, Historical Institute (MNE)

In 2017 a Joint Archaeological Laboratory was launched between the Italian National

Research Council and the University of Montenegro, Historical Institute, which aimed

at studying the city of Doclea and its territory. Particular attention was devoted

to the transformations in topography and the evolution of specific monuments between

the Roman imperial period and the early Middle Ages (4th-7th c. AD). After a building

phase, probably dating to the Diocletian age, well documented phenomena in other Dalmatian

cities and in the Roman world in general are encountered, such as the abandonment

of public buildings and their reuse. Common phenomena include the conversion of buildings

for artisanal use, the change in the orientation of the roads and the construction

of Christian churches.

This contribution illustrates the data that has been collected so far by an Italian-Montenegrin

team, employing a multidisciplinary approach. Since the site was excavated from the

end of the nineteenth century, work began with the collection and analysis of historical,

archival and epigraphical data, and is now proceeding with archaeological, architectural,

topographical and geophysical field research. In such a way it is now possible to

begin to trace the transformation of the city during Late Antiquity.

This paper presents the preliminary results of a longstanding project, carried out by an international team of Italian and Montenegrin researchers, that deals with the study and enhancement of the Roman archaeological site of Doclea.

Thanks to a series of bilateral projects between the Institute of Science of Cultural Heritage of the National Research Council of Italy (ISPC‑CNR) and the Historical Institute of the University of Montenegro (HIM‑UoM), with the participation of the University Federico II of Naples and the University of Molise, our work in Montenegro was able to begin in 201511. For an overview (…) . Funding for it came from the CNR and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (MAECI), together with the support of the Italian Embassy in Montenegro and the Embassy of Montenegro in Rome.

Excavated mostly at the end of the 19th century, Doclea is one the most prominent archaeological sites in Montenegro. Nevertheless, it is still inadequately studied and promoted22. For an overview (…) .

Built in the northwestern sector of the wide Zeta plain upon which Podgorica is also located, the town was the second-largest of Roman Dalmatia. This lowland at the confluence of the Morača and Zeta rivers and the Širalija stream (fig. 1), marking the end of the Bjelopavlići (or Zeta) valley, seems to have been associated in antiquity with important cultural and commercial exchanges, that connected the northern and western Balkans with Albania and northern Greece. The Doclea area, therefore, represented for millennia a key point for pre‑Roman, Roman and later communities, all of whom were attempting to control the passage from the northern and eastern mountains towards the western and southern flatter zone, leading to the Skadar Lake and the Adriatic coast (fig. 2).

© Lucia Alberti.

© Bruna Di Palma and Marianna Sergio.

The Doclea area was conquered by Octavian in 35 BC and a few years later became part of the province of Dalmatia33. For the history (…) . Named after the Illyrian tribe Docleati, Doclea was founded and then created as a municipium in the 1st century AD. The town occupied a smaller area of about 25 hectares, forming almost a triangle with imposing walls that enclosed a large forum, a basilica, various temples, tabernae, domus, an impressive complex of thermae, along with many other buildings of different sizes all of which are still visible. Several necropoli and tombs surrounded the town. Although the town was destroyed by the Avars in the 7th century, Doclea still retained an important late antique and medieval phase, represented by the remains of three medieval churches (fig. 3).

The red colour highlights the structures already reported in the surveys of Munro et al. 1896, plate IV and Sticotti 1913, plate outside the text, later destroyed or seriously compromised by the construction of the railway viaduct and the modern road; the circuit of the walls is schematically indicated in black.

© Antonio D’Eredità in Sfameni et al. 2022, fig. 1.

During the pre‑Roman period, before the foundation of the town, the remains are mostly concentrated in the surrounding hills, where at least two Illyrian gradinae have been found, in the Doljanska Glavica and Trijebač hills. They enjoyed a very dominant position in the valley, controlling the roads and the Zeta plain from the north to the Skadar Lake44. Mlakar 1960; Ga (…) . Outside the walls of the Roman town, several tumuli have been discovered as well as a few Early Bronze Age stone tools and pottery fragments. Inside the Roman city, in the southern part, near the temple to Diana, at a depth of about 80 cm, excavations conducted by the Centre for Conservation and Archaeology of Montenegro (Centar za konzervaciju i archeologiju Crne Gore)55. https://www.cka (…) have brought to light fragments of Late Bronze Age pottery, along with some Illyrian finds and several coins dated «to the reign of the Illyrian King Ballaios and Queen Teuta of the Ardiaei, a tribe who ruled in the mid‑second century BC»66. See the Report (…) .

The first researchers in Doclea were Russian, British and Italian. At the invitation of Prince Nicholas of Montenegro, the Russian archaeologist P.A. Rovinski conducted the first systematic excavation in 1890-1892 bringing to light the Roman basilica, the thermae, and the so‑called first and second temples and the temple of Diana, part of the walls and other buildings (fig. 4). In 1893 the British archaeologist J.A.R. Munro discovered the late antique and early medieval Christian churches77. Koprivica 2013, (…) . After having visited the site after the first excavations, the Istrian researcher P. Sticotti in 1913 published an entire monograph dedicated to Doclea, which is still one of the most important publications about the site (fig. 5)88. Sticotti 1913. (…) .

© Rade Koprivica, 2021.

© Sticotti 1913, plate outside the text.

During two World Wars research ceased. Then, in 1947 and against the wishes of the Italians, the Montenegrin state built a railway through the middle of the site, destroying sectors of the thermae and the temple of Diana99. Burzanović, Kop (…) . The railway, connecting Podgorica with Danilovgrad and Nikšic, is still in use today1010. For a new idea (…) .

Between the 1950s and 1970s more important discoveries were brought to light when the eastern necropolis was excavated and published by the University of Belgrade and Museum of Podgorica1111. Cermanović-Kuzm (…) .

After the first enthusiastic decades of excavations, with the discovery of large sectors of the forum at the end of the 19th century, together with more recent activities, Doclea was largely forgotten. Such a key‑site of Roman Dalmatia clearly needed a more integrated and global approach, and this was lacking.

In the last decades, some work by Montenegrin and international teams have been conducted, especially by the Centar, the results of which have been published in the journal Nova Antička Duklja1212. Nova Antička Du (…) . In 2007 a joint research project led by the British School at Rome (BSR) and the Archaeological Prospection Services of Southampton (APSS) investigated through magnetometry parts of the forum1313. Pett 2010, p. 1 (…) .

A few years later a mission from the University Ca’ Foscari of Venice investigated the late antique sectors, while the University of Urbino, in collaboration with the BSR and the municipality of Podgorica, worked on the photogrammetry and cartography of the site1414. Gelichi et al. (…) .

The first research of our Italo-Montenegrin team goes back to 2015-2016, with the first bilateral project carried out by the Institute of Heritage Science of the National Research Council of Italy (ISPC‑CNR) and the Historical Institute of the University of Montenegro (HIM‑UoM), following a first scientific agreement signed in 2013 between CNR and the Ministry of Science of Montenegro1515. Alberti, Sfamen (…) . A few months later, an agreement between the two countries was signed in the field of scientific research, followed by another one in 2014 with a specific reference to the Montenegrin cultural heritage1616. Alberti 2020, p (…) . In 2017, a Joint Archaeological Laboratory set up by the ISPC‑CNR and the HIM‑UoM started systematic activities in Doclea, with a multiplicity of scientific and cultural goals: firstly, the resumption of all studies carried out previously, with systematic archive and bibliographical research, secondly the application of the most innovative technologies applied to cultural heritage and the territory, and thirdly a project of enhancement1717. Alberti, Sfamen (…) . Particularly important was the 2018‑2022 period, with the Project of Great Relevance “The Future of the Past: Study and Enhancement of Ancient Doclea, Montenegro”, funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Italy (MAECI) and the National Research Council of Italy (CNR). The ultimate goal of this project was to give the Montenegrin authorities a credible and sustainable project of relaunching of the site, in order to revitalise not only Doclea, but also the area in which it is located1818. Di Palma, Alber (…) .

Today, research in Doclea is continuing in the framework of a second Great Relevance Project, again funded by MAECI and CNR, with the title “Ancient and modern routes along the river valleys of Montenegro: from remote sensing and landscape archaeology to the enhancement of cultural sites and itineraries”. We are working on the cultural itineraries and sites that punctuate the great valleys of the country, connecting the archaeological remains with other cultural itineraries, to enhance also minor cultural heritage sites. Our goal is to investigate, in particular, the ancient road networks along the fluvial valleys of Montenegro, involving other Roman municipia as Municipium S near Pljevlja1919. Di Palma, Alber (…) .

Last but not least, one of our goals is also the dissemination of the results, with a special reference to younger generations. In this framework, we recently published a volume on Doclea, aimed at adolescents and published by the Montenegrin Ministry of Education as the first book of a new monograph series dedicated to the Montenegrin cultural heritage2020. AAVV 2022. (…) . From the beginning of our research in Doclea, together with ISPC‑CNR and HIM‑UoM, the Institutions involved were the Department of Architecture of the University Federico II of Naples, and the University of Molise, with their researchers in geophysics. A brief collaboration was undertaken also with the Centar in 2020‑20222121. Alberti 2020. (…) . Other specialists working at the site include historians, archaeologists, remote sensing experts, topographers, conservators, and architectural designers.

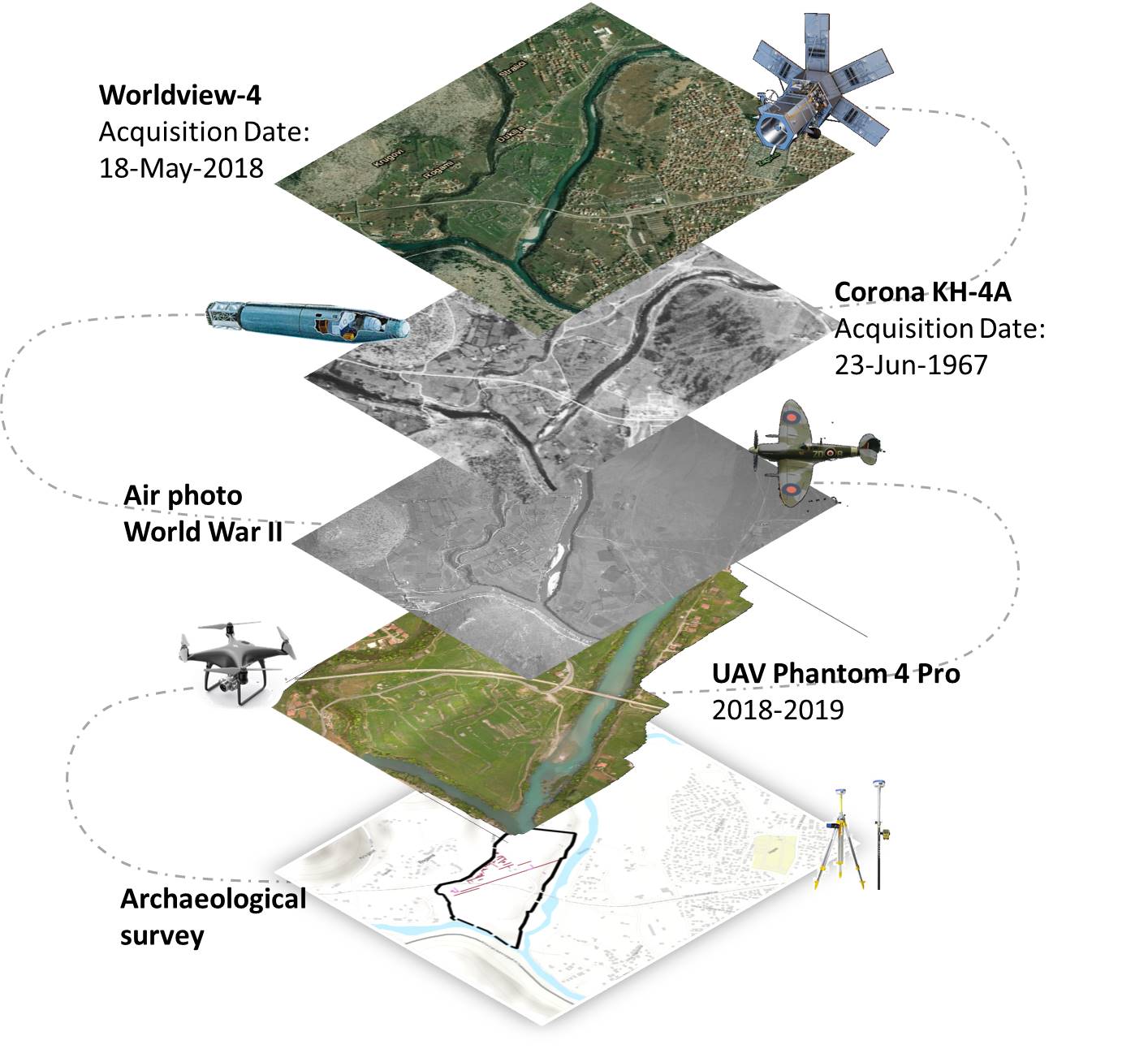

Our integrated methodological approach, with its different levels of analysis on different scales involving both humanities and applied technologies, is based first and foremost on archival and bibliographic research, something that modern technology cannot replace. In conjunction with this we use satellite, aerial and drone data (remote sensing), archaeological survey and landscape archaeology on the earth’s surface, and finally underground to geophysical prospections (fig. 6). Only after this process of mutual exchange among different expertises and approaches, is it possible to establish a credible project of enhancement.

© Pasquale Merola.

In depth research was initially conducted by the Montenegrin team focusing on the collection of records and archaeological finds kept in several European archives and museums. Particularly interesting were the 19th and 20th century traveler’s diaries2222. Koprivica 2013; (…) .

The scientific analysis began with remote sensing. During the archaeological photo-interpretation phase of remote dataset, several processing techniques were employed. Of particular use was a 1942 aerial photo of the Italian army during the II World War, different satellite images, and aerial drone shots at various elevations. We investigated the variations affecting both the vegetation status and the soil’s physical, and other features, such as thermal conductivity and capacity. The obtained images were analyzed from an archaeological and topographical point of view. Here, the objective was to interpret all traces in an attempt to reconstruct buildings and structures which were no longer visible, the urban system and the organization of the surrounding area2323. Colosi, Merola, (…) .

In order to verify the remote sensing data, several campaigns of archaeological survey have been conducted on the Doclea plateau, resulting in an almost total coverage of the area. Where walls emerged, they were positioned using a differential GPS.

Several campaigns of geophysical prospections through Ground Penetrating Radar have been conducted by our team, covering the majority of the town inside the walls (areas between the forum, the basilica, the Capitolium, the thermae and the walls of the city, around the eastern medieval churches, in the southern part of the temple of Dea Roma and of the private houses). The already published results were impressive (fig. 7)2424. Cozzolino, Gent (…) .

© Cozzolino, Gentile 2020, fig. 10.

After several campaigns of remote sensing, archaeological survey, and especially geophysical prospections, not to mention a synthesis of all the collected data, the urban layout of Doclea slowly emerged, albeit without archaeological excavation.

All the results obtained so far, together with the 3D reconstructions are contributing to the architectural planning of the valorization project, brought about thanks to the work of the architects from the Department of Architecture of the University Federico II of Naples. The main lines of the strategy adopted in order to re‑launch the area will be briefly outlined here2525. Prof. Bruna Di (…) .

The strategy collates archaeological research and themes of urban redevelopment and landscape restoration. The project deals with a beautiful and still uncontaminated landscape but also starts from the shape of the Roman urban layout. The new layout of internal routes, therefore, is based on the intersection of the decumanus and the cardo, and the perimeter of the defensive walls. In fact, at the points of intersection between the walls and these two main routes, some further strategic areas are identified and some buildings supporting the development of the site and the wider territorial framework have been inserted. In this strategy, site accessibility, the internal pedestrian circulation, the economic issues, and the general management have been taken into consideration (fig. 8)2626. Di Palma, Alber (…) .

© Bruna Di Palma.

Outside the walls, new paths and thematic itineraries involving not only environmental/natural aspects, but possibly other cultural/historical sites have been planned. In this process, we would like also to involve the local communities, in order to give new life to past material culture and traditions and to produce economic growth through sustainable tourism.

In agreement with the approach that “Archaeology is not the research of the past, but research, in the past, of a possibility for the present”2727. «L’archeologia (…) , our ultimate goal is to restore the collective memory of a community, between past and present, local and global, scientific and popular. In our view it is only by preserving and enhancing our common heritage, that we can also build a promising, credible ‘tomorrow’ also in terms of scientific archaeological research and sustainable tourism.

The final goal of our research, indeed, is not only to improve our understanding of Doclea from an archaeological and historical point of view, but it is also to complete its enhancement project. Our aim is to hand the site back to the local communities, so that they can use it as a tool for improving their cultural and socio-economic situation. What we understood in recent years is that if an ancient site is not ‘adopted’, used and in some way ‘loved’ by the local community, our work is incomplete and does not achieve the result of the diffusion of culture.

The integrated analysis of the remote sensing images, geophysical data, and the findings that emerged during the archaeological survey made it possible to formulate some preliminary hypotheses on the urban layout of Doclea.

In the central area of the city, intended for public civil and religious buildings, the decumanus maximus represents the most evident sign of urban planning. The road crosses the city from west to east in a marked straight line, which has also left a clear trace on aerial photographs2828. Alberti, Colosi (…) . From the western gate, where the presence of an honorary arch probably dedicated to Gallienus is documented2929. Sticotti 1913, (…) , the decumanus runs through the forum area, flanked by the main monuments, crosses the cardo maximus at the height of the so‑called Capitolium and then continues up to the limits of the plateau on the river Morača (fig. 9). Here, P. Sticotti reports the presence of a tower and a gate in the walls, while on the opposite bank of the river, part of the specus of an aqueduct was excavated in the early 20th century (Fig. 5, n° XIII)3030. Sticotti 1913, (…) . The infrastructure reached the left bank of the Morača after traveling approximately 14 km from the spring of the Cijevna river. According to T. Turković, the aqueduct is the result of an intervention by the Emperor Diocletian, given that it is locally defined as "Dukljanov vodovod" and presents a structure and a particular method of construction almost identical to that of the aqueduct in Split3131. Turković 2021, (…) .

On the aerial photo the trace of the decumanus maximum is clearly visible along the entire plateau. The alignment continues beyond the Morača River.

© Bruna Di Palma.

The decumanus maximus of Doclea had an imposing aspect: in the stretch between basilica and Capitolium ‒ that is, in the public and monumental part of the city ‒ its width, including sidewalks, was 15 meters, while the paved road itself measured 10 meters (fig. 10). In front of the complex of structures extending west of the basilica, the north side of the decumanus appears to be set back by approximately 3.70 meters, possibly due to the presence of a portico or an open space.

© Alberti, Colosi, Merola 2020, p. 12, fig. 6.

A covered walkway, perfectly visible from geophysical anomaly maps, flanked the road on the south side (fig. 7, a‑b)3232. Cozzolino, Gent (…) . The presence of the portico was confirmed by an excavation carried out by the Centar in 2018, which highlighted the base of a column and three floor levels (fig. 11). The first layer can be dated to the 1st century AD, the second at the end of the same century, when the town became a municipium, while the third, in compacted earth, dates back to the 4th century3333. Živanović 2018b (…) . It is possible that the three archaeological layers correspond to different phases of the urban layout of Doclea, with the one at the end of the 1st century coinciding with a rise in the street level by about half a meter.

A column base lying on the southern border of the road is visible.

The cardo maximus, on the other hand, is probably 10 meters wide, including space for sidewalks. Its dimensions likely corresponded to those of the other road axes of the town, as reconstructed according to a topographical survey and geophysical prospections3434. Colosi, Merola, (…) .

In the central public sector of Doclea and south of the decumanus maximus, remote sensing analysis and survey data made it possible to reconstruct an urban layout articulated on a regular grid of square blocks, each with a side length of 59 meters (200 Roman feet). (fig. 7, C)3535. The use of squa (…) .

This layout was confirmed by the results of a geophysical analysis: in 2017‑2018, the Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) prospections conducted by the CNR team south of the private house and Diana temple, highlighted clear anomalies referable to probable road axes and building structures with north-northeast ‒ south-southwest and east-southeast ‒ west-northwest orientations (fig. 7, a, b, 1‑2)3636. Cozzolino, Gent (…) . In 2008 the magnetometry surveys of the British School mission highlighted traces of probable residential quartiers in the southwestern part of the plateau. The survey revealed negative features corresponding to limestone walls, defining rooms grouped around a possible courtyard. Inside the rooms, a very high signal of positive anomalies «represent either an in situ floor within the rooms or a collapse layer of the roof and walls leading to a deposit of brick and tile within the walls of the building». Based on the acquired data, English geophysicists have reconstructed in the area, two insulae separated by a cardo (fig. 12) that measure approximately 70×80 meters3737. See Pett 2010, (…) . The excavation tests carried out by the Centar in 2018 confirmed the presence of a residential area in the southern part of the town, with the discovery of well-preserved pottery at floor level3838. Živanović 2018b (…) .

© Pett 2010, p. 35, fig. 12.

East of the cardo maximus, the interpretation of the GPR anomalies indicates a probable change in dimension of the insula, highlighting the limits of a 75 m wide block, which corresponds to a module of approximately 2 actus, very widespread starting from the Augustan age, especially in the cities of northern Italy and Adriatic area (fig. 7, C)3939. Cozzolino, Gent (…) . This dimension corresponds to that of the north-south side of the forum, which measures exactly 75 m.

In the absence of further stratigraphic data, it is not possible to determine whether the variation in dimensions could correspond to different chronological phases of occupation on the plateau. However, if the presence of the 70×80 m insula identified by L. Pett were confirmed, it might suggest a difference in module between the central, public area of Doclea and its more peripheral, residential zones in the southern and eastern sectors.

Furthermore, in the area around the churches, geophysical surveys have registered a clear change in the orientation of the blocks in north-northwest ‒ south-southeast and west-southwest ‒ east-northeast directions4040. Cozzolino et al (…) , highlighting that «around the churches, high amplitude values are sparser compared to the other areas, perhaps because in this peripheral zone the concentration of buildings was lower»4141. Cozzolino et al (…) . These anomalies could be interpreted as an urban planning intervention connected with the late antique phase of the city, witnessed by the sacred buildings (fig. 7, a, b, B‑C)4242. G. Hoxha (2021, (…) . At the moment, this hypothesis is not supported by the excavation data. Corresponding to the geophysical anomalies, a 2nd century wall came to light in the area west of the churches, along with three rich layers of fine ceramics dating back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD4343. Živanović 2018a (…) . This phase of life in the area is further supported by the discovery of remains of an older building in the narthex of Basilica B, with fragments of Roman ceramics and coins from the Aurelian age4444. Stojkovic 1957, (…) . An isolated tomb from the 4th century could indicate that the area was not occupied by houses at this time, while the excavations have not identified any further traces of late antique occupation4545. Živanović 2018a (…) .

Based on of the data acquired by Centar, in the 2nd and 3rd centuries the housing sector of the city developed in the southern and especially in the eastern part of the plateau. Here, starting from the cardo-decumanus system, regular blocks were generated. Along the northeastern strip of the city, urbanization was less dense and the layout changed direction, perhaps due to morphological and water flow reasons, which later influenced the course of the city walls and, in the 6th-7th centuries, the construction of the churches4646. For the descrip (…) .

Montenegrin archaeologists believe that from the beginning of the 4th century, when Doclea was surrounded by walls, the life of the citizens was concentrated in the southwestern sector, where the insulae were occupied by residential buildings and urban villas4747. Živanović 2018a (…) .

In recent articles T. Turković states that the public center of Doclea was rebuilt and monumentalized by Diocletian. The emperor decided to completely transform the city, embellishing it with new public buildings and public spaces so that he «built a new town in the place of the old one»4848. Turković, Marak (…) . According to the scholar, it is possible that during this phase the urban layout of the southwestern part of the city adopted the strict orthogonal grid based on a 200 feet module. Even if Doclea «certainly had an urban outlook from the beginning»4949. Turković 2021, (…) , Diocletian’s intervention was so incisive that it really does look like he «rebuilt the center of his hometown from a scratch»5050. Turković 2022, (…) .

As already mentioned, further investigations would be necessary to date with certainty the urban layout and its possible chronological evolution. However, we agree with Turković that the current plan of Doclea is the result of a long process of development, as shown by the changes in orientation and size of the blocks documented in our fieldwork. An example of the transformations in urban planning over time can be observed in the altered road scheme north of the forum, as identified through GPR prospection. In this area the cardo that runs between the forum and the Capitolium appears to change direction, bending eastward towards the m3 gate, coinciding with the passage of the cardo maximus. This change in the route of the road likely occurred when the city walls were constructed, allowing the road to exit the city through the main northern gate (fig. 7 c, G15, G16)5151. The magnetometr (…) .

The process of evolution is confirmed by a widespread phenomenon observed in the southwestern sector of the city: the late occupation of road sectors by new constructions. Indeed, parts of certain public and private buildings extended beyond the boundaries of the blocks, as exemplified by the bath sector of the private house, occupying the southern side of the decumanus. This suggests that the bath dates to the late antique period (fig. 13, B; fig. 30, 31)5252. Colosi, Merola, (…) .

In red, the ancient structures that overlap the Roman roads.

© Colosi, Merola, Moscati 2019, p. 70, fig. 6.

Furthermore, the enclosure of the private temple appears not to respect the width of the insula. In Sticotti’s plan of the complex, two perpendicular walls made of squared stone blocks are depicted, aligning with the boundaries of a paved area along the eastern cardo. These walls likely belong to an earlier phase than the one visible today (fig. 13, C; fig. 31)5353. Sticotti 1913, (…) .

Along the eastern side of the public baths, some rooms added to the original building and dating back to the 4th century AD overlap the roadway (fig. 13, A; fig. 14)5454. Colosi, Merola, (…) . The large bathing complex is characterized by four construction phases which run between the 1st and 4th centuries AD (see par. 5). Turković refers to these phases as an example of the city’s urban evolution, rightly noting that the results of geophysical surveys capture a snapshot that «is just an end result of a long process of development of the town, and not its entire history»5555. Turković 2021, (…) . Unfortunately, we don’t know exactly in which moment of the 4th century the eastern rooms were built, but it certainly occurred after the urban layout was planned5656. For a synthesis (…) .

© Antonio D’Eredità in Sfameni, D’Eredità, Koprivica 2019, p. 98, fig. 10.

Even the layout of the forum, as Turković points out, interrupts the regular streets: on the east side, the apse of room A, probably dating back to the last phases of the complex (see par. 5, fig. 16), invades the cardo (fig. 13, D). Finally, the structures on the western side of the basilica present different phases of construction. Their belonging to the later phases of some rooms facing the decumanus is confirmed by the presence of an apse that partially occupied the public open space.

The continuity of the urban layout’s orientation, accompanied by the failure to respect the road axes and the block’s width, constitutes a widespread phenomenon in the transformation of public spaces in cities during the late antique period5757. Liebeschuetz 20 (…) . This process, already highlighted by Wilkes in the case of Salona5858. Wilkes 1969, p. (…) , may represent additional evidence of Doclea’s vitality in the 4th century, when the western sector of the city was involved in various public and private building developments5959. A strong buildi (…) .

The site’s structures have been severely compromised by spoliation and destruction over the centuries, right up to recent times: most of the walls do not exceed one meter in height, while decorative elements are scarce and scattered across the entire area and are often far from their original position. In the absence of excavation data, it is necessary to start from a precise analysis of the structures to try to identify the late antique building phases. Some transformations are evident in the main buildings of the city’s monumental sector, but it is difficult to assign a specific period to them. Some information can be obtained from bibliographic and archival documentation, and all the interpretative proposals developed by scholars who have studied Doclea over time remain important.

Using drone photos, photogrammetric systems and total station surveys, we are creating new detailed plans of the buildings and the city, while also attempting, where possible, to highlight the different phases. During our work, we are observing significant differences in the structures compared to the plans provided by Sticotti (fig. 14)6060. Sticotti 1913. (…) . At this moment, we are specifically studying the surviving architectural decoration in detail in order to also propose new reconstructive hypotheses of the main monuments6161. Work in progres (…) .

Data of particular interest concerns the city walls that follow the natural limits of the plateau. The northern section of the fortifications is imposing, with walls reaching almost 4 m in height, while the sections along the Morača and Zeta rivers are less well preserved6262. Work in progres (…) . The main access gate to the city was located in the western part of the walls along the road that led to Doclea from Diluntum and Narona (fig. 15). This section of the fortification includes materials from various monuments and more than twenty inscriptions. Among these, there are six imperial dedications, which according to P. Sticotti were originally set up in the basilica in the forum6363. Sticotti 1913, (…) . The latest inscription was dedicated to Valerian and dates to 2546464. Sticotti 1913, (…) , and therefore in his opinion the construction of the fortification wall must post date the end of the 3rd century6565. Sticotti 1913, (…) . J. Wilkes agreed that at least this part of the fortifications would have been built or rebuilt in the 3rd century or later6666. Wilkes 1969, p. (…) . Based on a direct analysis of the structures, M. Živanović and A. Stamenvović believe that «the construction of the city walls of Doclea took place under the patronage of a Roman emperor in the second half of the 3rd and during the 4th century»6767. Živanović, Stam (…) .

© Francesca Colosi, 2023.

Relevant data on the late antique phases of the city can be obtained from the area of the forum, the basilica, and the building complex to the west (fig. 16). Doclea’s forum is large, almost square in shape and surrounded by porticoes and buildings (total area 59×75 m), except on the south side, which is closed by a continuous wall with two entrances via the decumanus maximus6868. Sticotti 2013, (…) . The central area of the square was originally paved with stone slabs, now completely lost (fig. 17).

© Antonio D’Eredità in Sfameni, D’Eredità, Koprivica 2019, p. 98, fig. 11.

© Sticotti 1913, fig. 57.

The western side of the square is entirely occupied by a large rectangular building, commonly interpreted as a basilica, while on the north and east sides there are rooms of different shapes and functions. The latter have been identified alternatively as tabernae (shops) or scholae (headquarters of priestly or trade associations). On the northern side, a square podium is prominently positioned and aligned with the main entrance on the southern side. Many scholars have proposed differing interpretations of this structure: J. Wilkes suggested that it may have functioned as the curia of the senate6969. Wilkes 1969, 37 (…) , whereas other scholars speculate that it could have served as a small temple, potentially dedicated to the imperial cult7070. Turković 2021. (…) .

J.A.R. Munro pointed out that the rows of shops along the northern and eastern sides could be of very late date, incorporating fragments such as cornices and architraves from the basilica7171. Munro et al. 18 (…) . P. Sticotti also noted that a fragment of the basilica’s cornice was repurposed as an entrance threshold to a room with an apse in the middle of the eastern side, where a burial was discovered7272. Sticotti 1913, (…) .

The direct analysis of the forum structures reveals a complex history marked by multiple phases of alteration and repurposing. It is difficult to definitively ascertain the original functions of specific rooms and spaces, particularly since the original decorative elements such as painted walls and mosaic or stone flooring have been completely lost.

Among the main interventions, in a room on the northern side, a wall was inserted to close off a threshold in the apse. The apse in the middle room of the east side is a later addition, which occupies the main cardo (fig. 18). The burial found inside the apse, rather than being that of a distinguished individual, as some scholars supposed, could be a later addition in the last phase of the structure. In the same part of the building, the closure of numerous thresholds also indicates modifications to the original layout and passage between adjoining rooms (fig. 19). Unfortunately, precise dating of these interventions is challenging, but they reveal extended use of the forum complex with functions that changed over time.

© Carla Sfameni, 2023.

© Carla Sfameni, 2023.

The construction of the forum is generally attributed to the Flavian age. Such a dating is based on inscriptions on an architrave with a dedication of an equestrian statue by the ordo Docleatium in honour of M. Flavius Balbinus, son of M. Flavius Fronto and his wife Flavia Tertulla (fig. 20)7373. CIL III 12692. (…) . According to P. Sticotti, the statue could have been placed in front of the basilica, on a pedestal that bore a more detailed dedication to the boy, which, unfortunately, is now lost7474. CIL IIII 13820. (…) .

© Carla Sfamen, 2021.

Re‑evaluating the documentation concerning Doclea’s forum and basilica, T. Turković, suggests in a recent study that these structures formed a unified complex to be attributed to the emperor Diocletian7575. Turković 2021. (…) . The scholar argues that Diocletian likely undertook a comprehensive reorganization of Doclea, identifying it with the city where he was born. In this optic, Doclea’s “forum” ought to be viewed as an “imperial forum” for Diocletian’s court, a Caesareum for imperial worship7676. Srejović 1967 a (…) . The 4th‑century historian Sextus Aurelius Victor in his work Liber de Caesaribus writes that Diocletian, before becoming emperor, was called Diocles after his mother and the city of Dioclea7777. Ps. Aur. Vict. (…) . Additionally, Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, in the 10th century, attests that a town called Diocleia took its name from a city founded by the emperor Diocletian: in his time the city, although abandoned, still had this name7878. De Administrand (…) . These sources offer many intriguing clues which suggest that Diocletian’s influence on the region was strong. However, the emperor’s origins remain uncertain. All we can say is that he was Dalmatian and perhaps born in Salona7979. Wilkes 2009. Th (…) . Thus, Diocletian’s direct involvement in Doclea cannot be proven8080. For new argumen (…) .

The western side of the square is dominated by a rectangular building featuring a large apse on its northern end, which is commonly interpreted as a basilica8181. Sticotti 1913, (…) . This structure was accessible from the eastern side of the square, while on its southern side three windows opened onto the decumanus. The building’s architecture included a single nave supported by buttresses along both long sides. The hall was subdivided into distinct sections: a central rectangular area was the largest part of the building, measuring 50×13 m. At each end of this central area were rectangular sections that likely had entrances with two columns supporting an archway: to the north, a large door led into an apsidal hall measuring 13×10 m (fig. 21). Originally, this hall had a mosaic floor, then overlaid with marble slabs8282. Rovinski 1909, (…) . Inside the apse, there was a raised section, possibly intended for seating8383. These details a (…) . J.C. Balty suggested that this hall served as the curia, where senate meetings were held8484. Balty 1981, p. (…) . The apsidal hall is connected to a spacious rectangular room on the western side. Unfortunately, no traces remain of the original floors or decorations within these rooms, making their appearance challenging to reconstruct. However, the layout suggests a significant ceremonial or administrative function for this part of the forum complex, likely playing a central role in civic or government activities.

© Carla Sfameni, 2023.

The western side of the basilica was characterized by masonry pillars that reinforced the structure on both sides, with openings towards the western area (fig. 22). According to Sticotti, bases of statues were originally placed against the pillars with dedications to emperors, ranging from Alexander Severus (226‑227 AD) to Gallienus (268 AD), which were later reused in the construction of the western city walls8585. Sticotti 1913, (…) .

© Carla Sfameni, 2023.

The eastern wall of the basilica, facing the forum with five openings, is now completely destroyed. Only the bases of some external pillars remain, while the columns which once adorned the façade have disappeared. According to P. Sticotti’s reconstruction of the façade, the architrave bearing the inscriptions of Flavius Balbinus would have been positioned over the doors, with semicircular windows above them closed by stone grilles8686. Sticotti 1913, (…) .

The basilica, dated by Sticotti to the first half of the 2nd century, has sparked scholarly debate regarding its architectural models and chronology8787. See Walthew 200 (…) . P. Sticotti draws comparisons with the Basilica Ulpia of Trajan’s Forum in Rome, and Diocletian’s Palace in Split8888. Sticotti 1913, (…) . However, due to the significant chronological gap between these structures, direct comparisons are questionable. J.C. Balty dates the basilica to the time of Trajan8989. Balty 1981, p. (…) , while, according to I. Stevović, the building underwent renovations between the late 3rd and early 4th centuries, along with the main baths of the city9090. Stevović 2014, (…) . Renovations are indicated by the existence of two different overlapping floors, and by repairs to the eastern wall of the apsidal room using masonry brick.

Some Corinthian capitals found in the basilica, characterized by intricate acanthus leaves rendered with deeply drilled engravings (fig. 23) are similar to those in Diocletian’s Palace in Split. These capitals suggest a construction or renovation phase possibly dating to the late 3rd century AD, possibly even during Diocletian’s reign. The architectural decoration, particularly the use of archivolts on the colonnades, also points towards a timeframe around the end of the 3rd century AD.

© Antonio D’Eredità, 2017.

T. Turković argues against associating the basilica with examples from the Julio-Claudian and Trajanic periods, proposing instead comparisons with the forum of Cyrene and other sites dedicated to the imperial cult9191. Turković 2021. (…) . According to the scholar, the architecture of the basilica exhibits, in particular, distinct characteristics of the Tetrarchic period.

However, uncertainties remain regarding the architrave with dedications, which dates to the Flavian period; the decoration of the architectural cornices is also referable to the Flavian era, if not earlier. Further research is needed to clarify the earlier phases leading to the construction of the basilica and the other structures within the complex. Our research group is currently conducting a comprehensive review of the available documentation to delve deeper into these inquiries. This effort aims to shed light on the historical context and chronological sequence of developments associated with the basilica and its surrounding structures.

To fully understand the development and functions of these buildings, it is also essential to consider the structures located on the western side of the basilica9292. Sfameni, Kopriv (…) . Here a large quadrangular area contained numerous buildings, some of which appear contemporary to the forum-basilica complex, while others were probably constructed or modified later. Research in this area has been conducted in 1962, 1998, and 1999 but detailed excavation reports have never been published, making it exceedingly complex to reconstruct the building phases and determine the functions of these structures (fig. 24).

© Administration for the Protection of Cultural Properties, Cetinje, Doclea Excavations Documentation, 1998.

Within a large rectangular space, it is possible to distinguish two main areas. The first sector of elongated rectangular shape is adjacent to the basilica and was accessible from it through three doorways with steps. A rectangular space was attached to the southern wall; according to T. Turković, this space might have constituted the podium of a temple, and the entire area would have had a sacred significance9393. Turković 2021. (…) . In front of the southern wall, there was a room which was probably built upon the foundations of an older building during Rovinski’s excavations and used as a storage space for archaeological tools and as a custodian’s residence.

The second part of this extensive area towards the west has been variously interpreted by scholars. Some of them view it as a section of a private residence opening onto a central courtyard9494. Turković 2021, (…) , while others suggest it might have served as a market space9595. Rinaldi Tufi 20 (…) . A portico with corner pilasters and two central columns underwent modifications, including the closure of the spaces between the columns in a later phase. The rooms situated between the portico and the main street also belong to a later phase (fig. 25), likely contemporaneous with the transformation of the portico. The presence of an apse that partially occupied the decumanus, further confirms a later construction phase for these structures. These rooms likely had residential purposes, suggested by the presence of a small heating system, which was possibly a private bath. These spaces could have been adapted within pre-existing areas originally associated with the portico. Additional rooms were located in the far western sector of the excavated area, with many walls exposed, particularly in the northernmost section.

© Administration for the Protection of Cultural Heritage, Cetinje (1962).

A temple structure was excavated in 2005 in the area east of the forum9696. Baković 2010; B (…) . The temple is a tetrastyle prostyle of about 8,5×15 m closed on the west, south and east sides by small rooms with porticoes (fig. 26). The main access to the sanctuary was on the south side on the decumanus, and geophysical surveys identified traces of a colonnade along the cardo on the western side9797. Cozzolino et al (…) . The atrium was paved with limestone slabs, while the cella had a black and white mosaic with geometric patterns.

© Carla Sfameni, 2021.

The main interpretation of the temple as the capitolium of the city9898. Baković 2011. N (…) has been questioned due to its lack of a tripartite cella and its location outside the forum. Within a series of rooms created in the porch surrounding the building, significant traces of craft activities, particularly metalworking and glass processing, have been discovered. In room 3, a first phase was identified between the second half of the 1st and the beginning of the 2nd century AD. In the 2nd-3rd century the space performed ceremonial functions; in the late phases the room became the site of an artisan workshop9999. Živanović 2011. (…) . Metalworking activities began in the first half of the 4th century, after the temple was already abandoned. By the end of the 4th and the beginning of the 5th century, a glass workshop was established in the same location. However, glass production ceased in the early 5th century, shown by the absence of typical forms from the 6th-7th centuries. The end of production may have been due to practical reasons, as there are no signs of destruction or fire in the craft workshops. It is also plausible that some artisans relocated to other parts of the city100100. Živanović 2014. (…) .

In a recent paper, T. Turković suggests that these artisanal activities were connected to the cult venerated in the temple, possibly that of Minerva101101. Turković 2022. (…) , In the temple of Allat-Minerva in Palmyra, which has a building phase dating back to the Diocletian age, for example, Minerva was associated with the production of sacred weapons. The scholar attributes a small pediment with the depiction of a deity with a helmet, otherwise interpreted as the “dea Roma” to this temple (fig. 27). The exact place of discovery of this pediment is not known, but it is generally connected with the so‑called first temple or temple of the dea Roma102102. Sticotti 1913, (…) . Discussing this hypothesis would require more detailed analysis, on the basis of the stratigraphic data provided by the Montenegrin archaeologists. Moreover, among the fragments of architectural decoration present on the site near the podium, there is a part of the pediment, which suggests that the pediment with the image of the helmeted goddess was not used in this location.

© Carla Sfameni.

In front of the forum, on the south side, there is a large bath complex. In describing the latter’s architectural structure and decoration, now disappeared, Sticotti hypothesized the function of many rooms in the west part, as a vestibule, a gymnasium, a frigidarium and some calidaria (see fig. 14)103103. Sticotti 1913, (…) . Unfortunately, the entire south-western sector was destroyed by the railway, and it is therefore not possible to reconstruct a precise plan of the complex104104. Sfameni, D’Ered (…) . According to J. Wilkes, who dates the complex to the Flavian age, the baths of Doclea would be more luxurious and imposing than those of Salona105105. Wilkes 1969, p. (…) . Archaeologists who excavated the area in 1997-1998 highlighted multiple building phases evidenced by overlapping wall structures, with the latest phase dating to the 4th century (fig. 29)106106. Administration (…) .

During our research we highlighted the presence of these different construction phases, examining the position of the walls (fig. 28)107107. Sfameni, D’Ered (…) . A final phase, moreover, is attested in particular in the eastern area where some rooms occupy part of a paved area along the city’s cardo (see par. 4).

© Antonio D’Eredità in Sfameni, D’Eredità, Koprivica 2019, p. 99, fig. 12.

To the east of the main complex lies another bathing complex known as the small baths, excavated in 1962 and barely published (fig. 29)108108. Only brief repo (…) . Here, there are various rooms with basins and hypocaust heating, which originally must have had a mosaic floor. Based on archaeological finds, the baths date to the 4th century, but according to some scholars they were used longer than the large thermae, right up until the 5th century AD109109. Srejović 1968, (…) . Geophysical research indicating the presence of an intermediate courtyard, demonstrated that these structures were connected to the preceding complex (see par. 4; fig. 7)110110. Cozzolino, Gent (…) .

© Carla Sfameni, 2023.

Unfortunately, the first and third temples on the south side of the decumanus are now completely destroyed, but information about them can be drawn from P. Sticotti’s descriptions and plans111111. Sticotti 1913, (…) . In particular, the so called third temple was attributed by P. Sticotti to Diana due to the discovery of a pediment with the goddess’s image112112. Sticotti 1913, (…) . Recently, T. Turković and N. Maraković proposed that the temple was actually dedicated to Diana Agrotera and Apollo Delphinios: this attribution is based on limestone slabs depicting dolphins and other elements found at the site113113. Turković, Marak (…) . This temple would also have been built in the era of Diocletian, but this attribution and date require further discussion.

The residential areas situated south and west of the decumanus are not well documented, although topographical surveys identified numerous walls. The only fully excavated house consists of over twenty rooms arranged around a courtyard (fig. 30). P. Sticotti attributed this domus to the Flavian period, which, given its location and the presence of a small temple in an adjacent enclosure, he deemed to be an elite residence (fig. 31)114114. Sticotti 1913, (…) . However, the bathhouse associated with this domus was constructed later, and is characterized by a more irregular construction technique. Furthermore, a room of this complex was built on part of the decumanus. Thus, the bath could be a late antique addition.

© Antonio D’Eredità, 2019.

© Sticotti 1913, p. 78, fig. 37.

In a recent study, A. Oettel and M. Živanović propose identifying this house as a statio beneficiarii associated with a temple precinct dedicated to Rome, where imperial cult practices took place115115. Oettel, Živanov (…) . The scholars attributed the relief depicting the female deity with a helmet and aegis (the so called dea Roma) to this temple. It is noteworthy that in the same volume of the New Antique Doclea series by the Museums and Galleries of Podgorica (2022) the same piece is interpreted differently: as we have seen, T. Turković identifies it as Minerva, placing it on the pediment of the so‑called capitolium. Oettel and Živanović, however, suggest it represents the goddess Rome, to be associated to the little temple. This variety of interpretations underscores the ongoing scholarly interest in Doclea and the importance of further study of its monuments. However, it seems very important to us to verify the hypotheses with a careful study of the archaeological documentation: for example, as regards the relief of the “goddess Rome”, the off‑center positioning of the clypeus on the pediment indicates a side view rather than a frontal one, suggesting that it adorned a temple accessed laterally.

In recent years, archaeologists from the Centar uncovered a room with an apse heated by a hypocaust system on the north side of the decumanus (fig. 32)116116. Živanović 2018a (…) . They believe it served as a reception room in an elite 4th century residence. In the apse it is possible to recognize the structure of a stibadium, which constitutes evidence in favour of a late antique date.

© Carla Sfameni, 2023.

From this preliminary examination, it appears possible to recognize in the main buildings of Doclea two different forms of intervention in Late Antiquity, the first of construction or reconstruction of structures, and others involving abandonment and reuse. Finally, the construction of buildings of Christian worship marks the transformation of the urban space of the city.

In 1893, the British archaeological mission in Doclea enriched the picture provided by the excavations of Rovinski and produced a more complex representation of the site’s greatness and significance. In the eastern part of the city, the team led by J.A.R. Munro discovered the late antique and the early medieval Christian churches – known today as Basilica A, Basilica B and the Cruciform church117117. Munro et al. 18 (…) . Regardless of the fact that Munro’s excavation offers no precise information on the identification of strata or the ubication of fragments of architectural sculpture, and putting aside the occasional mistakes of his interpretations, all together, accompanied by the photographic documentation made in the course of his exploration, they constitute a prerequisite source for the study of sacral topography of Christian Doclea118118. Koprivica 2013; (…) . The results of the British research increased the interest of the general scientific community in Doclea.

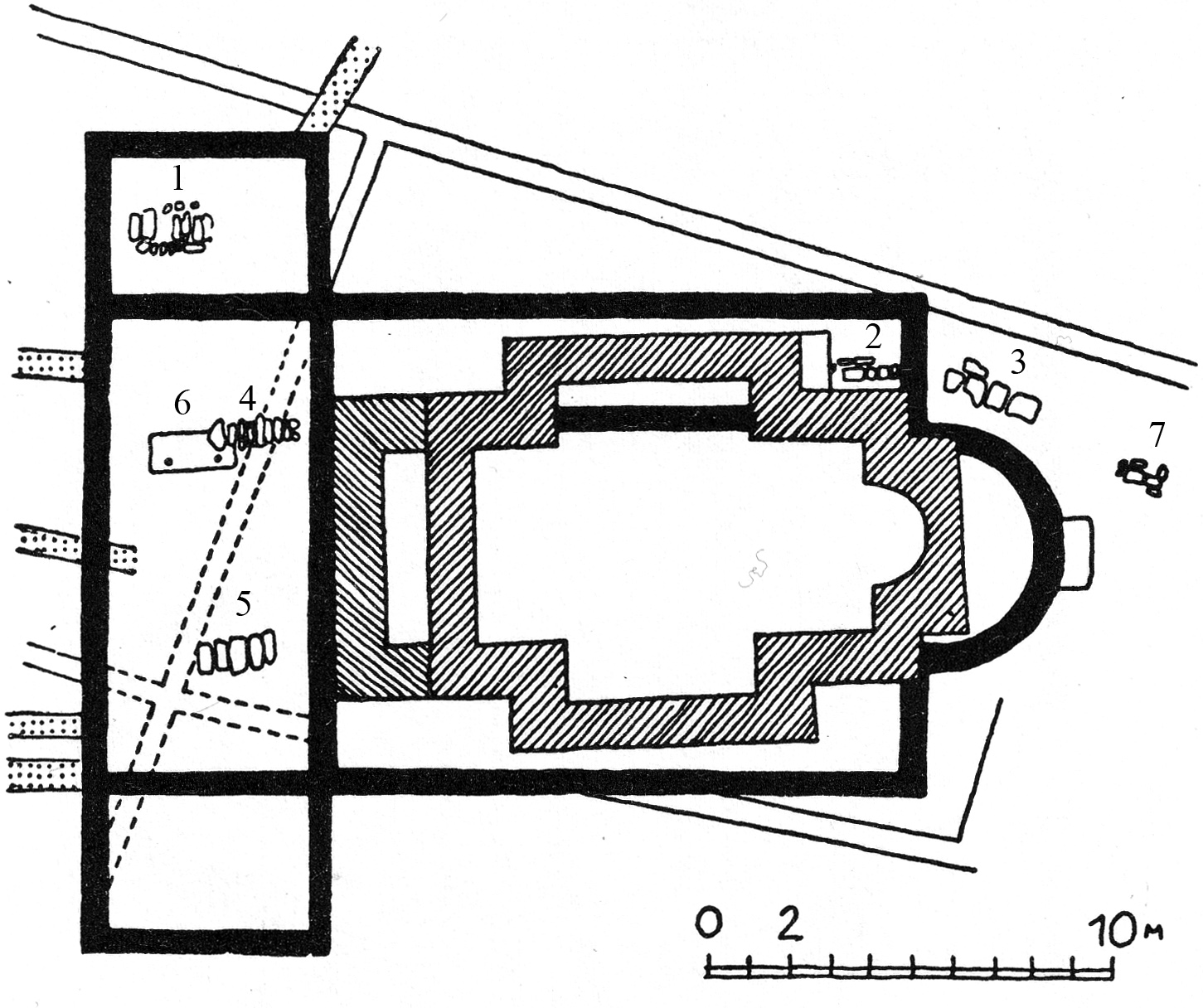

The Christian complex in Doclea, consisting of the Basilica A, Basilica B and Cruciform church connected by a corridor, is in a very poor condition today (fig. 33).

© Rade Koprivica, 2021.

Research on ecclesiastical buildings, with a survey of the structures, a census of the construction techniques and a review of the stone materials, was conducted by a team from the Ca’ Foscari University of Venice directed by S. Gelichi119119. Gelichi et al. (…) . In the context of our research projects, we paid particular attention to the area of the churches, and from a direct analysis of the archaeological remains, we propose a new plan as well as some reconstructive hypotheses of the churches’structures120120. Sfameni et al. (…) .

Basilica A is a three‑nave basilica whose dimensions are 34×17 m (fig. 34). The height of the extant walls is between 0,90 and 1,50 m. The apse, on the east, is semicircular on the inside and hexagonal on the outside. The built‑in seats with the spaces for the bishop’s chair were arranged around the apse. Next to the apse, there are the diaconicon and the prothesis (fig. 35)121121. Munro et al. 18 (…) . The schola cantorum was in front of the apse (fig. 36).

© Rade Koprivica, 2021.

© Elisa Fidenzi, after Sfameni et al. 2022, p. 375, fig. 3.

© Koprivica 2013, p. 7, fig. 3.

The British archaeological mission in 1893 excavated the balustrade coloumns, finely sculpted pieces of marble slabs, a large number of crosses, window grills (transennae), capitals (one Ionic with a cross, several impost capitals and two of the Corinthian order, identical to those from the civic basilica on the forum) «and other byzantine carvings» (fig. 37). J.A.R. Munro organized the workers who «arranged the fragments, capitals, columns, etc. in a fancy way which may puzzle the archeological visitor».122122. Koprivica 2013, (…) Thus, the fragments were removed from the original locations on which they had been found. On the grounds of the report put together by British archaeologists and a revision of the site carried out in 1954, all the sculpture from Basilica A was dated to the pre-Justinian’s era123123. Nikolajević-Sto (…) .

© Koprivica 2013, p. 8, fig. 4.

In 1893, mosaic flooring was found to have been preserved throughout the entire space of the basilica. Worst preserved was the mosaic in the naos and the best was in the southern nave (fig. 38). W.C.F. Anderson described them thus: «The patterns interlaced spirals, or diamonds and squares and are worked out in some five or six colors»124124. Koprivica 2013, (…) . There is no trace of this decoration.

© Koprivica 2013, p. 12, fig. 12.

A short distance from the wall running parallel to the wall of the cruciform church lay the south wall of the atrium. These are most probably the remains of the bishop palace.

The propileum was built 30 m from the entrance of Basilica A, which stood at the end of a corridor leading to an area with a complex series of different ecclesiastical buildings. An initial place of Christian worship was then rebuilt and replaced by Church B and then by a Cruciform Church125125. Stevović 2014, (…) . The Christian sacral core of Doclea is similar to that of Salona or Tragurium (Trogir), where likewise two connected churches existed.126126. Stevović 2014, (…)

It is considered that Basilica A represents the Episcopal church of Doclea. It is not known when the Episcopate was established. Some scholars assumed that the first known Doclean bishop Basus was appointed in 325 or 326127127. Kovačević, 1967 (…) . Based on the primary and secondary sources, it has been found that the bishop Constantine of Doclea took part in the Council of Ephesus in 431 and that the bishop Evander of Doclea took part in the Council of Chalcedon in 451. The last known bishop of Doclea was Nemezian, who, in 602, replaced the bishop Pavle128128. Kovačević, 1967 (…) .

Basilica A can be dated from 4th to the middle of the 6th century. At least, two construction phases are visible. It is not known when Basilica A and the Christian complex in Doclea was destroyed.

Basilica B was built above the remains of an older Roman architectural structure (fig. 39)129129. Gelichi et al. (…) . The slanted wall, considered by J.A.R. Munro to be the edge of an undiscovered street, was, in fact, the outer wall of a building which extended towards the central point of the complex comprising two churches. Remains of walls of a third building, older than Basilica B, were discovered in the course of a reopening of the narthex floor (fig. 40). The inner space of this structure was divided into several units. The presence of a number of different strata was confirmed also by an exploration carried out in 2011130130. Gelichi et al. (…) .

© Rade Koprivica, 2021.

© Istorija Crne Gore I (J. Kovačević).

Basilica B is a three aisled basilica whose dimensions are 18,5×11,5 m with the semicircular apse in the east and narthex with two lateral compartments in the west The height of the extant walls is between 0,60 and 1,20 m.

The Cruciform church was later built into Basilica B (fig. 41). The church has the design of a free cross, with somewhat shorter transept. Several inscriptions were found inside the Cruciform church131131. Koprivica 2013, (…) .

© Elisa Fidenzi, after Sfameni et al. 2022, p. 399, fig. 14.

Although J.A.R. Munro in 1893 discovered both the Cruciform church and Basilica B, his interpretation of the two was incorrect. P. Sticotti already identified two different periods of construction and noted that the cruciform church had been erected on the foundations of Basilica B132132. Sticotti 1913, (…) . In the course of revision excavations of 1954, it was discovered that Basilica B was of the three-nave type133133. Nikolajević-Sto (…) . A spatial unit was found in the south part of the narthex, corresponding to that at the north end, which had already been discovered by J.A.R. Munro. The flooring unearthed in the center of the narthex was present in all three spaces.

Based on its architectural structure and sculptural decoration, Basilica B can be dated to the 6th century, although according to some it might also be 5th century134134. Nikolajević-Sto (…) .

The east part of the Cruciform church was square in plan, with a semicircular apse of inferior quality masonry. A three feet high sculpted cornice was found by the north wall of the church. A small-scale closed space was located by the north wall of the church and a threshold with a column base at its center was found in situ in its southern wall135135. Koprivica 2013, (…) . This column base is clearly visible on a photograph from 1893136136. Stričević 1955, (…) .

The wall in front of the western wall of the Cruciform church in 1893 had a threshold with column bases on both sides and a perfect “nest” of pillars, capitals and other architectural fragments pillars, capitals and other architectural fragments (fig. 42)137137. Koprivica 2013, (…) . These, together with the fragments discovered in the course of the excavations of 1954, were divided into two groups. The first was made up of surface fragments located around the Cruciform church, while the other included finds from the stratum of Basilica B, which were discovered under a layer of Byzantine roof tiles. The scant amount of architectural sculpture, examined only on the basis of style, convinced earlier researchers that all these features dated to the mid 6th century.138138. Nikolajević-Sto (…)

© Koprivica 2013, p. 14, fig. 18.

Among the fragments, «facing the west end of the Baptistery», was the architrave with the votive inscription of diaconissa Ausonia139139. Munro et al. 18 (…) . The reference to Ausonia’s sons in the same inscription shows that she most probably entered the order after the death of her husband, since female deacons were exclusively virgins or widows140140. Sanader 2013, p (…) . What is certain is that Ausonia was the founder of some Christian building, erected pro voto to herself and her sons, or more precisely, as the family endowment built on her private property. In theory, it may well have been located in one of the densely populated extramural areas, where the remains of villas with churches were found141141. Nikolajević-Sto (…) .

Inside it and around the Basilica B and Cruciform church seven graves were discovered, one of them (n° 6) containing a preserved piece of cloth with gold thread woven into it142142. Korać 1955, p. (…) , clear proof that some dignitary was buried there.

##M. Cozzolino conducted the geophysical research in the western area of the medieval churches, noting that in this area there was a lower concentration of buildings with different orientations (see paragraph 4)143143. Cozzolino et al (…) .

A church, almost identical to the Basilica B, is preserved in Doljani, less than 3 km south-west from Doclea144144. Borozan 2000, p (…) . This complex is very important for our understanding of the sacred topography in the area surrounding Doclea.

However, almost nothing more precise could be said about the period when the cruciform church was built nor about the reasons that resulted in its position inside the older basilica. P. Sticotti compared the Cruciform church with the Mauseoleum of Galla Placidia, while I. Stevović compared it with the Church of Holy Trinity in the zone of Agrinio145145. Sticotti 1913, (…) . Some scholars identified the Cruciform church with the Church of St. Mary which is mentioned in the Chapter 9 of the Ljetopis popa Dukljanina (Chronicle of the Priest of Doclea) and which used to be the coronation church for the kings of Doclea146146. Kovačević 1967, (…) . The dating varies from the 6th to the 9th century147147. Sfameni et al. (…) .

The Cruciform church in Doclea, erected above Basilica B, could testify to a reduction of the city`s sacred focus, but could also attest a renewal of an ancient cult place148148. Stevović 2014, (…) .

There are still some open questions concerning the chronology and relationships between Basilica A, Basilica B and the Cruciform church149149. Sfameni et al. (…) . The precise dating of the individual buildings, as well as of the Early Christian complex in its entirety, requires further systematic archaeological investigation.

At several sites around Doclea, burials were found. The largest concentration is in the eastern necropolis, where burials occurred from the 1st to the 4th century, while burials at the western necropolis took place from the 4th to the 6th century150150. Sticotti 1913, (…) .

At the Bjelovine site, near the western necropolis of Doclea, in 2013‑2014, a necropolis covering an area of over 2000 square meters was discovered on the property of the Vučinić family151151. The results of (…) . More than 80 graves were excavated, four of which, with barrel vaults, were dated to between the 4th and 7th centuries (fig. 43). On the east wall of tomb number 7, a cross was engraved, and on tomb number 11, there is a cross with the letters Alpha and Omega, along with the depiction of a nave. Fragments of older buildings were used in the construction of the tombs. I. Medenica suggests that the Podgorica cup may have been found in a tomb similar to those investigated, dating to the 5th‑6th centuries152152. Ivana Medenica: (…) . M. Živanović believes that the tombs date to the 4th‑5th centuries, and that some fragments of engraved glass with a figurative decoration found inside them are stylistically close to the famous Podgorica cup. According to the same author, one of the tombs was likely reused later, not as a burial site but perhaps as a gathering place for early Christians153153. Živanović 2015, (…) .

In 2024, in the western part of the town, outside the walls, the researchers from Centar have recently conducted new excavations in a sector of the necropolis. In the preliminary report they refer to the discovery of 171 graves154154. Živanović, Živa (…) .

© Tatjana Koprivica, 2023.

Epigraphic sources are crucial in our understanding of early imperial Roman Doclea as they give us insights into the social structure, demography, population mix155155. Pelcer-Vujačić (…) and religion156156. Koprivica 2020, (…) . Unfortunately, the epigraphic evidence for late antique Doclea is much more limited, and this poses a challenge for specialists attempting to reconstruct the social, economic, and cultural aspects of the city during this period. In publications and digital databases, many inscriptions are generically dated to the 3rd century, but could also belong to the earlier period. Most of the 3rd century inscriptions are honorific for emperors and members of the imperial court (dated from 226 to 260 AD), such as Severus Alexander157157. CILGM 149 = CIL (…) , Philip the Arab158158. CILGM 102 = CIL (…) and his wife159159. CILGM 151 = CIL (…) , Gallus160160. CILGM 150 = CIL (…) and his son and co‑ruler C. Vibius Volusianus161161. CILGM 152 = CIL (…) , Valerian162162. CILGM 146 = CIL (…) , and Gallienus163163. CILGM 147 = CIL (…) . Five of them suffered damnatio memoriae and were largely eradicated. These actions indicate once again the instability and volatility of the 3rd century Roman Empire.

Funerary inscriptions from Doclea and the surrounding area, dated to the 3rd century and later, are rare and three of them show classic epigraphic traits: Roman names, and life span in years, months, and days164164. CIL III 8282; C (…) . Interestingly nearly all of them commemorate women, offering insights into the roles and recognition of women within the society of Doclea. This gender-specific epigraphic evidence contributes to a broader understanding of social dynamics and family structures during this era.

One funerary inscription from Vuksanlekići dated to the 3rd century has radically abbreviated names, so not much can be deduced165165. CIL III 14603 (…) :

V(---) T(---) et V(---) O(---) et / A(---) P(---) f(ilius?) sibi et / s(uis) v(ivi) f(ecerunt)

The only inscription dated to the early Byzantine period is the famous one about deaconess Ausonia166166. CIL III 13845; (…) :

Ausonia diac(onissa) (p)ro voto suae et fili(o)rum suoram f(e)c(it)

The inscription under discussion is presently considered lost, with its last documented sighting in 1902 by P. Sticotti167167. Sticotti 1913, (…) . At that time, the artefact had been partially disassembled, with a section of the inscription removed, after which it was repurposed as construction material for a local farmhouse. Consequently, the only surviving record of the inscription is in the form of drawings and a photo in Munro’s photograph album of Doclea168168. published by Ko (…) . Originally located at the entrance of a small cruciform structure in Doclea (identified as the Cruciform church), positioned on the west facade, its historical context and significance have been a subject of scholarly inquiry.

Debate surrounding the dating of the inscription has been particularly contentious. Initially attributed to the 6th century upon its discovery, subsequent analyses have offered divergent assessments. In 1957, Stojković-Nikolajević proposed a revaluation, suggesting an 9th century origin169169. Stojković 1957, (…) . However, this view was later revised back to the 6th century170170. Stojković 1981, (…) . Presently, the prevailing consensus in academic literature supports a 6th century dating, although alternative perspectives exist. Some scholars advocate for a date extending into the 7th century171171. Auber 1986 (non (…) , while the Epigraphische Datenbank Heidelberg (EDH) broadly situates the inscription’s timeframe between AD 301 and 600, without specifying further172172. https://edh.ub. (…) .

The inscription mentioning Ausonia is often cited in debates about women’s roles in early Church services. Here, opinions vary widely: some scholars argue that women were equal participants in Church activities during the initial centuries of Christianity, while others question whether women were involved at all. We propose that Ausonia served as a deaconess in the early Christian community of Doclea, and probably sometime in the 6th century. This hypothesis is supported by the inscription, although definitive conclusions about the role and contribution of women in the early Church remain elusive.

Despite the diverse and multifaceted nature of the Roman Empire, the situation in Doclea likely mirrored broader trends within the Empire concerning female Church service. Women like Ausonia, through their religious work, often achieved greater freedom and rights, challenging the prevailing patriarchal norms. This suggests that Ausonia, along with other women in the early Christian era, played a significant role in the Church, contributing to a gradual shift towards greater female emancipation in religious contexts173173. More on Ausonia (…) .

Another common feature for the late antique period was the reuse of older inscriptions as building blocks, as seen in Basilica A and the Cruciform church174174. Koprivica 2013, (…) a phenomenon requiring more study175175. Coates-Stevens (…) . This use of spolia should not only be seen as a practical response to a lack of fresh building materials, it was also symbolic, reflecting the continuity and transformation of cultural and religious landscapes over time. The integration of older inscriptions might have been intended to imbue the new structure with a sense of sacred continuity and legitimacy. Nevertheless, the question still remains if there was any consideration of the past in this practise or whether it was just a matter of thrift176176. Coates-Stevens (…) .

Although late antique epigraphic evidence is scarce and one can presume that Doclea was in decline, the tombs from the south-eastern necropolis dating from the reign of Diocletian to Constantius II are remarkably elaborate177177. Cermanović-Kuzm (…) . The slow decline starts from the reign of Constantine as there are fewer luxury goods and objects in the tombs (an exception could be the famous Podgorica cup, dated to the middle of the 4th century178178. Živanović 2015, (…) or later, according to other scholars). Nevertheless, the graves from the early 5th century and later are still showing the city’s trade connections in the Mediterranean.

In conclusion, while epigraphic evidence from late antique Doclea is limited and often ambiguous, it nonetheless provides valuable insights into the city’s social hierarchy, religious practices, and economic conditions. The combination of honorific inscriptions, rare funerary epitaphs, and archaeological finds from the necropolis collectively enrich our understanding of this historical period. The continued study and interpretation of these sources are essential for a more comprehensive reconstruction of life in Doclea during Late Antiquity.

O. P.‑V.

In conclusion, the research conducted in Doclea by the Italian-Montenegrin team since 2017 has allowed us to analyze the surviving building structures and to collect new information on the articulation of the city, thanks to topographic, geophysical and remote sensing surveys. From a strictly archaeological point of view, the lack of excavation data for the most ancient research makes it difficult to confidently date the different building phases via their form and architectural decoration. However, the systematic review of the existing structures, with the help of bibliographic and archive documentation, allows us to identify and approximately date the main construction phases. Based on these results, we observe in late antique Doclea the existence of a building phase that can be dated between the 3rd and 4th centuries and concerns in particular the forum area and the thermae in the city centre. The city walls also pertain to this phase and recent studies have tried to associate other monuments of the city to the same period. The suggestion is to link this building phase to the age of Diocletian: even if the direct relationship with the emperor is debatable, his interest in this city is highly likely. The rise and prosperity of the city, attested by the archaeological data, is in fact probably connected with the administrative reform and the creation of the province of Prevalis by Diocletian179179. Stevović 2014. (…) .

It is difficult to establish how long the city centre maintained its vitality: the research carried out in the so‑called capitolium shows that the temple had already been abandoned at the beginning of the 4th century when the first craft activities sprouted up. For the other buildings we do not have precise excavation data. Nevertheless, numerous changes can be observed in many buildings of the public area, including the reuse of materials from these buildings in the construction of the churches starting around the end of the 5th c. or the beginning of the 6th.

L. Jelić noted that the last coins found in Doclea date to Honorius180180. In Sticotti 191 (…) : it could therefore be assumed that the city, conquered by the Goths, remained under their control until the time of Justinian, but it is not sure. Renovations of the structures could therefore date back to the Justinian age, and the development of the ecclesiastical quarter could be dated to this phase. The city must have had a certain importance throughout the 6th century, while the last written sources date back to the end of the century181181. As already obse (…) . It is generally believed that, following the attacks of the Avars and Slavs, in 609, the population of Doclea moved elsewhere. That said, no bishop is attested in Antivari before the 8th century; intermediate locations have been hypothesized, such as in Martinićka gradina (Danilovgrad), which was easier to defend182182. Marasović 2013, (…) .

Numerous processes attested in Doclea are common to many other late antique cities, such as the abandonment of public spaces, the reuse of some structures for different purposes, the construction of Christian religious buildings in an area far from the public centre of the city, but within the city walls183183. Liebeschuetz 20 (…) . In particular, a similar process is attested in Salona, where the churches were built in the eastern area of the city, the Urbs nova184184. On Salona, see (…) .

The scarce data available for the Byzantine and early medieval phases could depend on the abandonment of the city but also on the absence of systematic research, and for this reason, an excavation in the area of the churches would be particularly useful.

In this article we summarized the status quaestionis and briefly illustrated the methodology adopted by our research team, who over the years contributed to expanding the knowledge on the ancient city of Doclea. The research is still in progress and in the years to come new plans and surveys of the monuments and their construction phases will be published, together with discussion regarding our interpretative hypotheses. Nevertheless, the data that has been collected so far not only allows us to underline the importance of the city in the late antique period, and also to highligh the growing interest, at a local and international level, for one of the most important sites of Roman Dalmatia.

Finally, to return to the Doclea of today, all of our historical-archaeological research is aimed not only at providing visitors with a better understanding of the site, but also of improving its infrastructure, while creating a new cultural and physical space for the community.

Agamben 2019 = Giorgio Agamben, La voce, il gesto, l’archeologia, lecture held at Palazzo Serra di Cassano, Naples, 9th May 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qkvlp4hUpL4.

AAVV 2022 = AAVV, Rimski grad Dokleja (The Roman town of Doclea), Editor Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva, Podgorica, 2022.

Alberti 2019 = Lucia Alberti, «Before the Romans: The historical and geographical framework of the Doclea valley», in Alberti (ed.) 2019, p. 19‑33.

Alberti (ed.) 2019 = Lucia Alberti (ed.), The ArcheoLab project in the Doclea valley, Montenegro (Campaign 2017): archaeology, technologies and future perspectives, Archeologia e Calcolatori Supplemento 11, Firenze, All’Insegna del Giglio, 2019.

Alberti 2020 = Lucia Alberti, «Le attività del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche in Montenegro», in Carla Sfameni, Tatjana Koprivica (ed.), Archeologia italiana in Montenegro: storia e prospettive di una cooperazione scientifica, Bridges: Italy Montenegro series 2, Roma, CNR Edizioni, 2020, p. 125‑148.

Alberti, D’Eredità 2019 = Lucia Alberti, Antonio D’Eredità, «The future of the past. First perspectives for Doclea today», in Alberti (ed.) 2019, p. 105‑111.