The Anastasian Wall

James CrowUniversity of Edinburgh, UK

The Anastasian Wall, built under Emperor Anastasius in the early 6th century, served as a vital defensive structure for Constantinople, stretching 58.3 km from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara. This wall was created in response to threats from steppe invaders like the Bulgars. Strategically located 65 km west of Constantinople, it complemented the city’s Theodosian Walls, protecting not only the city but also its suburbs and crucial supply routes. The wall’s construction was massive, requiring 10,000 workers over five years. Its formidable design included a ditch, towers, and forts at intervals to control access. Despite the advanced defenses, historical records indicate that it struggled during attacks, notably the Kutrigurs’ raid in 559 after an earthquake compromised parts of the wall. Emperor Justinian later restored the wall, reinforcing Constantinople’s security until the 7th century, when it was eventually abandoned amid growing external pressures. The Anastasian Wall, often referred to as “Rome’s Last Frontier,” stands as a testament to Byzantine defensive architecture, securing the capital’s outskirts and crucial resources.

Le mur d’Anastase, construit sous l’empereur Anastase au début du vie siècle, était un ouvrage défensif majeur pour Constantinople, s’étendant sur 58,3 km de la mer Noire à la mer de Marmara. Érigé pour répondre aux menaces des envahisseurs des steppes comme les Bulgares, ce mur se trouvait stratégiquement à 65 km à l’ouest de Constantinople, complétant les murs Théodosiens de la ville et protégeant ses faubourgs et ses routes d’approvisionnement cruciales. La construction nécessita 10 000 ouvriers pendant cinq ans. D’une conception imposante, le mur comprenait fossé, tours et forts pour en contrôler l’accès. Malgré ses défenses avancées, il montra des faiblesses lors des attaques, notamment lors du raid des Koutrigours en 559 après qu’un tremblement de terre ait affaibli certaines sections. L’empereur Justinien entreprit des restaurations pour renforcer la sécurité de Constantinople jusqu’au viie siècle, lorsque le mur fut finalement abandonné face aux pressions extérieures croissantes. Surnommé « La dernière frontière de Rome », le mur d’Anastase témoigne de l’architecture défensive byzantine, protégeant les ressources et les alentours de la capitale.

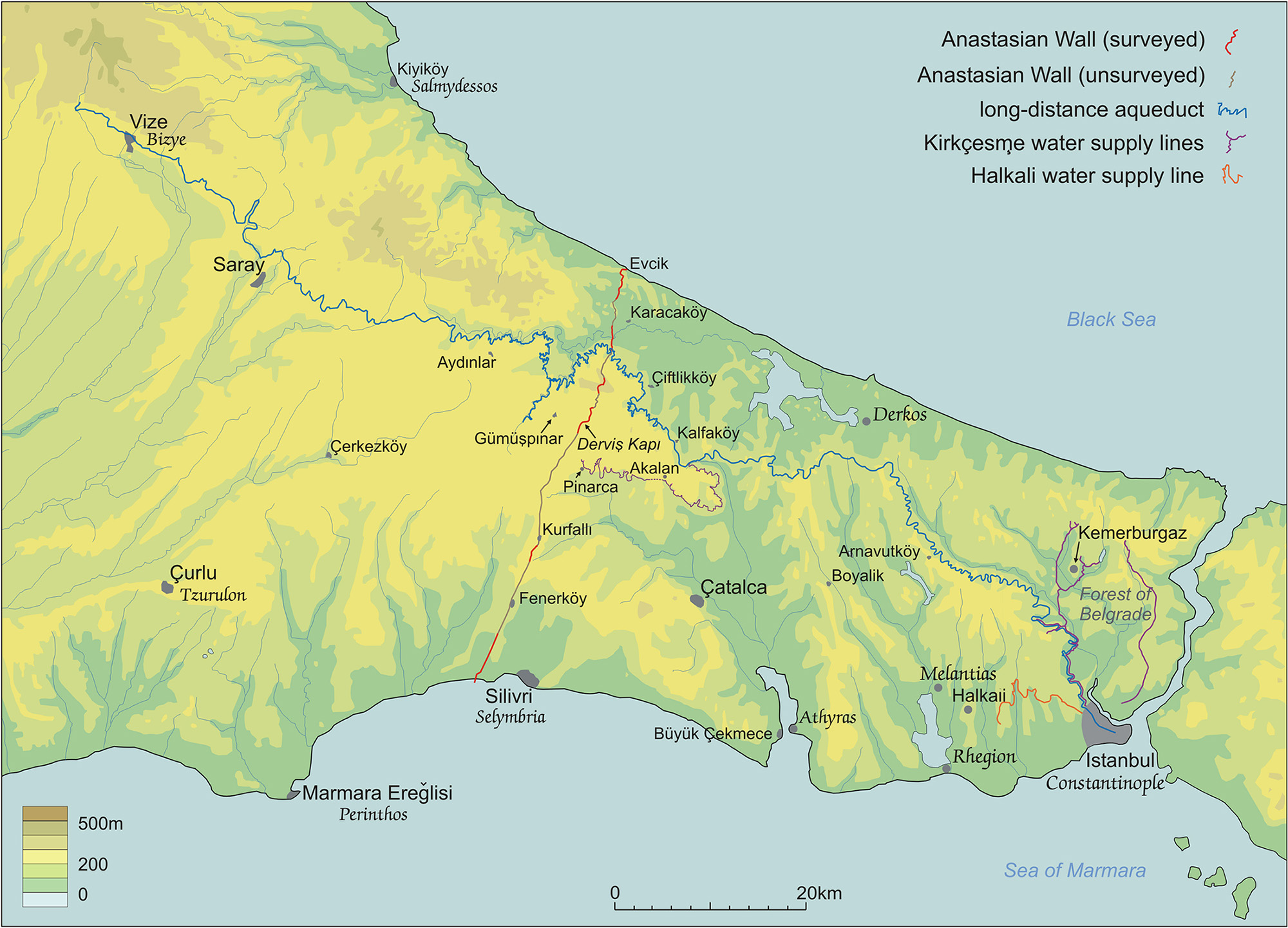

The great Theodosian land walls of Constantinople ensured the city’s security for nearly a millennium but outside its walls were other defences intended to ensure the wider protection of the city and its suburbs. Up until the early seventh century the main threat to Constantinople came from across the Danube. Within half a century of the city’s dedication the emperor Valens was slain and his field army defeated by the Goths at the battle of Adrianople (Edirne) in 378, barely 235 km from the eastern capital. It is hardly surprising that within two decades his successors embarked on the great land walls project11. Schneider, Meye (…) . However this massive undertaking was not deemed to be enough and early in the sixth century the emperor Anastasius created the last great liner barrier of antiquity, known as either the Anastasian Wall or the Long Walls of Thrace. Cities in eastern Thrace such as Selymbria (Silivri) near the Wall’s southern end and Perinthos/Heracleia (Marmaraereğlisi) were newly fortified in the mid-fifth century and they served as military strongholds along the main approach road to the city (fig. 1)22. Rizos, Sayer 20 (…) . But the Anastasian Wall served as a formidable barrier closing access from sea to sea across the peninsula for over a century.

© Richard Bayliss.

The Anastasian Wall was constructed 65 km west of Constantinople at the beginning of the sixth century AD probably in response to the increasing threat of new steppe invaders, the Bulgars33. Haarer 2006; Ho (…) . The wall stretches 58.3 km from the coast of the Black Sea in the north to the Sea of Marmara. A contemporary panegyric, praising the emperor’s achievements, claimed that, “What was the grandest and passes all imagination was to raise a high and powerful wall crossing all of Thrace. It passes from sea to sea, barring the route of barbarians, an obstacle to enemy aggression. The wall of Themistocles in Athens was smaller by report”44. Procopius of Ga (…) . A number of near contemporary sources such as Evagrius, Procopius of Gaza, Procopius of Casearea and the Chronicon Pascale attribute the construction to Anastasius and previous interpretations that construction began in the mid-fifth century may be dismissed55. Haarer 2006, p. (…) .

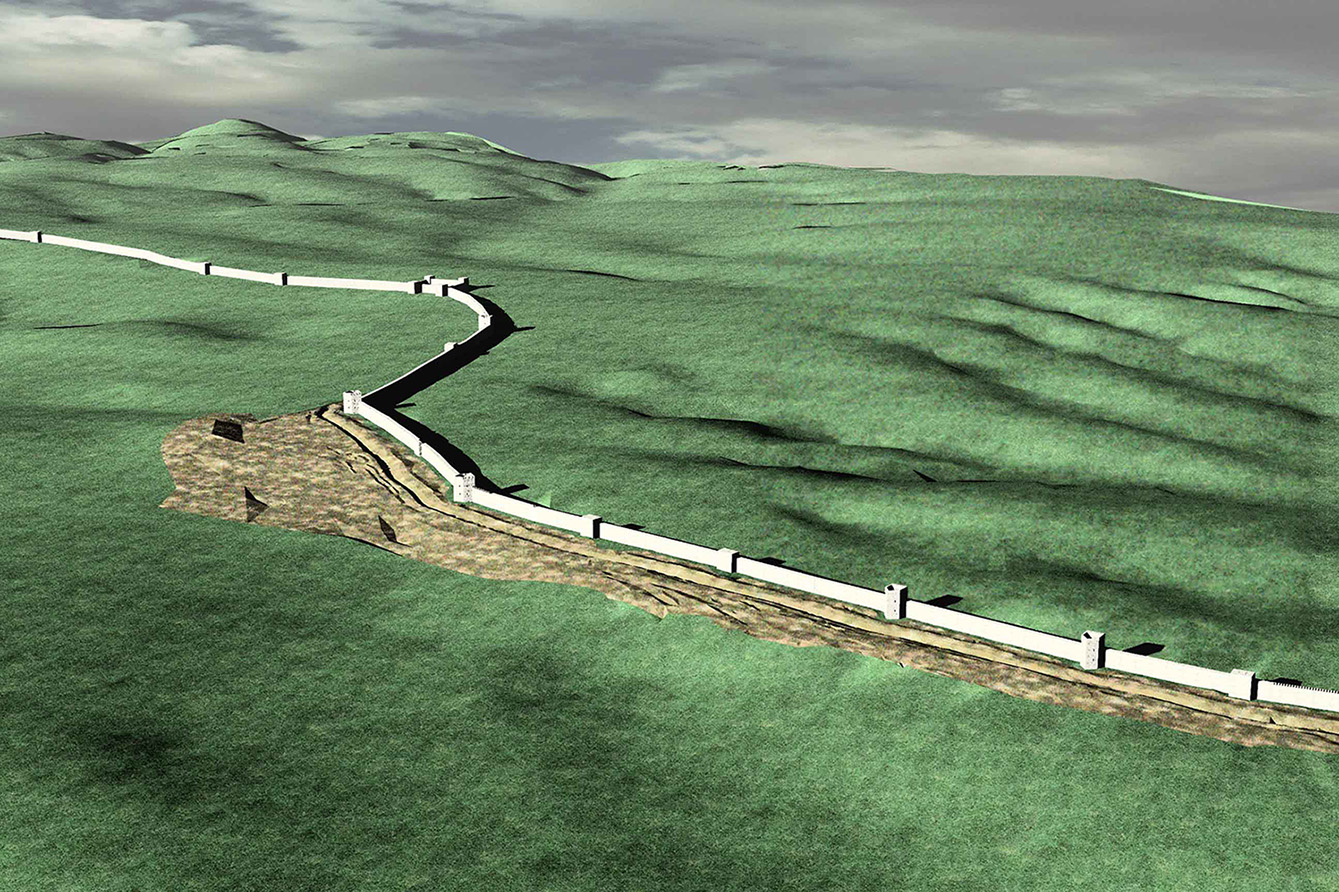

Survey between 1995-2003 has been able to map the line of the Wall and identify and plan small forts, towers and lengths of curtain surviving in the dense forest to the north66. Crow, Ricci 199 (…) . The southern sector of Wall runs across open, rolling hill-country, following a series of prominent north-south ridges ending at the Sea of Marmora 4 km west of the town of Silivri (Selymbria). Little survives for these first 20 km apart from a scatter of stone and brick in the ploughed soil (fig. 2). In places it is possible to identify towers and the low mound of the Wall itself. At the sea’s edge there is little trace on the beach, but within a few metres it is possible to discern the dark shadow of a long mole, less than 2 m below the water, representing a long probalos defence work constructed to prevent the wall from being outflanked along the shore. A similar feature is known at the south end of the Chersonese Wall across the Gallipoli Peninsula and its effectiveness was described by Procopius. In the southern sector south of the main railway line fragments of brick indicate that the wall may have been constructed of alternating courses of stone blockwork facings and brick courses, like the urban fortifications of Constantinople, and the nearby coastal cities of Selymbria and Heraclea. As the wall runs northwards, the ridges climb to a dissected plateau dominated by the high hill of Kuşkaya (378 m asl) (fig. 3) and run as far the cliffs overlooking the Black Sea at Evcik. These hills are densely forested with oak and beech, making an approach by an army difficult at any period77. Crow 1995, p. 1 (…) but also preserving long sections from extensive stone robbing.

© The author.

© The author.

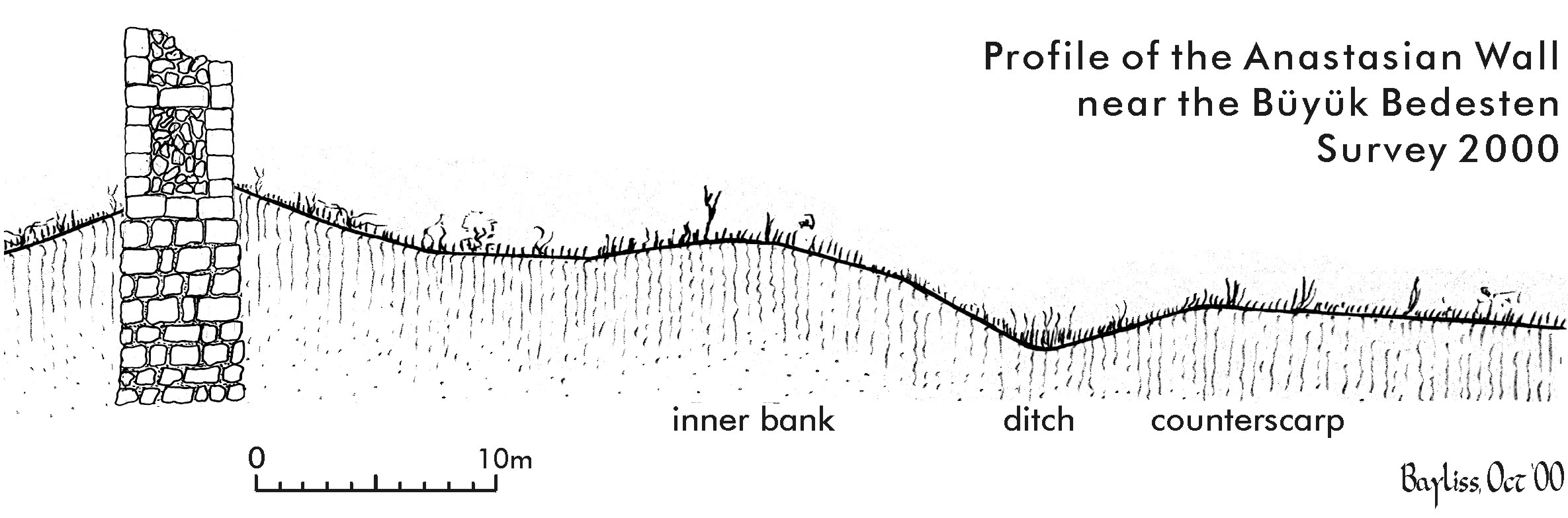

Where it survives best on the high ground, the Wall can be seen to have been constructed of large limestone or sandstone blocks with a core of limestone, or in some places metamorphic rocks (figs. 4, 5). The blocks and core are bonded with hard lime mortar with brick inclusions88. Snyder 2012. (…) . In most places the curtain wall is 3.20 m wide and the highest sections survive to a height of 4.5 m. In some sections the curtain was narrowed to 1.80 m with a series of internal arcades similar to sections of the sea walls of Constantinople and the outer wall (proteichisma) of the Theodosian land walls. Where the foundations are visible due to the futile efforts of treasure hunters or road construction they are seen to be 1.5 – 2.5 m deep. Essentially the structure of the curtain wall is similar to other late antique city and fortress walls. Surviving examples such as Resafa in Syria rise to over 10 m in height (Hof 2020a), and there is no reason to assume the Anastasian Wall was significantly lower. Except where the ground falls away steeply to the west as at Kuşkaya Tepe, there is evidence along the entire length of a ditch up to 15 m wide, with the outer lip located 23 m in front of the wall. Between the ditch and main curtain was a prominent mound (figs. 6, 7) comparable to the external mounds from the near contemporary Anastasian defences at Resafa in Syria99. Hof 2020a; 2020 (…) . At the small fort called the Büyük Bedesten a ditched outwork extends up to 80m in front of the fort and gate, this is probably a later defensive feature associated with invasions in the later sixth or seventh century (see below). It is one of the rare examples of earthwork defences associated with late antique fortifications, see the examples from Caricin Grad (Justinana Prima).

© The author.

© The author.

© Richard Bayliss.

© Richard Bayliss.

The curtain wall itself provided a formidable barrier and along its length was a system of towers. At points where the line of the Wall changes direction the towers were polygonal in shape, normally pentagonal, but in places hexagonal. These are massive structures, projecting over 11.5 m and were comparable to the largest towers from the ancient world1010. Crow, Ricci 199 (…) . These were clearly intended to provide platforms for torsion artillery. Agathias’ sarcastic criticism of the failure of the Long Walls to resist the successful assault led by Zabergan in 558/9, specifically mentions the absence of artillery defences, thus implying they were a normal feature of their defence:

There was nothing to stop them, no sentries, no engines of defence, nobody to man them. There was not even the sound of a dog barking, as at least would have been the case with a pig-sty or sheep-pen1111. Agathias, Histo (…) .

Between these great bastions were located numbers of wide rectangular towers, 11 m. wide but projecting as little as 2 m. to the exterior. One tower close to the modern road crossing at Derviş Kapı showed traces of double internal stairs and vaults (fig. 8). In the first phase there was an entrance 2.4 m wide, later narrowed to 1.5 m1212. Crow, Ricci 199 (…) . There is no surviving evidence for external stairs as found on the Theodosian Land Walls and the towers here were intended to provide accommodation and controlled access to the curtain wall. The towers were located at distances of 80-120 m apart suggesting that there would have been at least 340 towers along to the total length of the Wall.

© The author.

In addition to the regular system of towers there were also small forts, called locally bedestens. They are located at intervals of approximately 3.5 km apart and provided the main access points through the Wall. From the two planned examples (the Kücük [small] and Büyük [large] bedestens) these forts were constructed on the inner face of the wall, extending 32 m. behind the wall face and 64 m. parallel to the curtain. There were projecting rectangular towers at each of the angles. Midway along the two long axes was a gateway providing access into the fort and through the wall beyond (fig. 9). There is little evidence for structures within the enclosures and the evidence for permanent occupation was limited, suggesting that these forts were only occupied with small caretaker garrisons. With only limited crossing places and a high barrier probably 10 m. high the Long Walls will have created a major impact on local and long-distance movement for friend and enemy alike. In addition to the gateways at the bedestens there are likely to have been major defended gateways where major west-east roads crossed the line of the Wall. None of these are known, although the main one was located where the Via Egnetia crossed north of Silivri and possibly in the north where a road along the Black Sea coast is marked in the road itineraries.

© Richard Bayliss.

Construction by Anastasius was a massive undertaking but as noted before only brick stamps survive in the southern sector to materially document this work. The detail of the undertaking is unremarked in ancient sources but a doctoral study applying comparative energetics has contrasted the works on the fourth and fifth century Thracian aqueduct systems of the city with estimates from the known structures on the Long Walls1313. Snyder 2012. (…) . The estimates of materials and manpower are astonishing, concluding that despite the scale of the two aqueducts, each line amongst the longest in the Roman world, the construction of the Long Walls required five times the manpower required for the two phases of the aqueducts1414. Snyder 2012, p. (…) . Snyder estimated that a workforce of 10,000 was needed over five and a half years (2012, 254). Throughout Justinian’s reign when the Long Walls were adequately defended it resisted assault. As a measure of the Wall’s reputation for the inhabitants of the capital, the chronicler Malalas refers to it as “the Wall” of Constantinople (18.129), distinguishing it from the walls of Theodosius and Constantine (18. 124). Certainly it offered a measure of security for the settlements and farms outside the city’s land walls, but also a protected space for the main landwalls.

Procopius in the Buildings recorded extensive repairs to the Long Walls by Justinian when access to the towers were reduced and staircases were made inaccessible. The current scholarly consensus is that the Buildings was completed before 5541515. Sarantis 2016, (…) and the restoration may fall in the period after May 535 when Justinian created the newly established office of the Praetor of Thrace combining the previously divided roles of the civil and military vicars of the Long Walls1616. Sarantis 2016, (…) .

A number of historical texts concerned with both the great earthquake of 557-8 and the major raid lead by Zabergan and the Kutrigurs outside the Walls of Constantinople in the following year present differing perspectives on the Long Walls and their significance to the empire. They can be briefly summarised as follows: Agathias’s account of the Wall’s failure and his criticism of Justinian part of which was quoted earlier but makes no mention of the effect of the earthquake on the Long Walls, although in the same Book 5 he describes the seismic damage and subsequent collapse of the dome of Hagia Sophia. For Agathias the Kutrigurs passed through the Wall because it was allowed to decay and was unmanned through the emperor’s neglect. By contrast the account of Malalas, presented more fully in Theophanes’ Chronicle gives a quite different picture. For the year AM 6051 (558/9) the latter chronicle specifically states that the Huns “having discovered that some parts of the Anastasian Wall had collapsed through earthquake, they got in and took prisoners as far as Drypia and Nymphai”. The account continues with a description of Belisarius’ successful counter attack forcing Huns to withdraw beyond the Long Walls to western Thrace and eventually under the threat of the Danube fleet to retreat across the river Danube. Significantly Theophanes’ Chronicle continues by describing how after Easter the aged Justinian set up his court in Selymbria to personally oversee the restoration of the Long Walls. This was a remarkable event for an emperor who had rarely crossed the Bosporus and marks the importance of restoring the confidence of the citizenry of Constantinople in their Long Walls. During his stay the walls of Selymbria were also restored and this can be confirmed by brick stamps and specific forms of brick strengthening elsewhere only attested in the Justinianic phase of the restoration of the walls of Antioch (fig. 10). Theophanes observes that the emperor left the city shortly after the Easter festival only returning in August. The exact date of the imperial return is known from another fragmentary text found in the Book of Ceremonies. Recording the triumphal entrance of the emperor on 11 August 559 Justinian processed into the city paying tribute at the memorial of his wife Theodora in the Church of the Holy Apostles and onto the Great Palace. The triumph was presumably over the Kutrigurs forced to return beyond the Danube, but the dates present us with a rare timetable for an imperial building project from a few days after 13 April to 11 August 559. Time spent to ensure the continued outer security of the city by restoring its Long Walls.

© The author.

The investment seems to have paid off since despite increasing threats from a new steppe power, the Avars, the Walls and city were secure until the end of the century. In the coup against Phokas, the threat of Heraclius’ fleet at Abydos caused the Long Walls defenders to retreat to the city, clear demonstration both of their vulnerability, but also the failure of their previous attackers to mobilise any naval capacity.

The only known building inscription from the Wall refers to the emperor Heraclius and the patrician Zmaragdus. It was later reused in the construction of the small church perched above the Black Sea at the north end of the Wall at Evcik. The poorly carved text provides the latest dating evidence for reconstruction after 610, probably in response to the so-called Avar Surprise in 623, works supervised by the former exarch of Ravenna, Zmaragdus. However it seems likely that only a few years later the defensive line was abandoned before the Avar siege of Constantinople when the Eastern Roman Empire faced war on two fronts and the emperor campaigned in the east1717. Crow 2021. (…) . There are no further references for active use and it seems the Long Walls could no longer be manned effectively and subsequently fell into decay; later inscriptions noted by previous studies can be related to other fortresses in the region not the Anastasian Wall.

In the sixth century the construction and maintenance of the Thracian wall and other linear barriers marks a practical and pragmatic solution to increasing insecurity across the Balkans. By securing the pinch-points for communications it was possible to defend wider regions with more limited garrisons. Such a strategy contradicts Procopius’ claim that

Wishing as he (Justinian) did to make the Danube the strongest possible line of first defence before them and before the whole of Europe, he distributed numerous fortifications along the bank of the river1818. De Aed. IV I 33 (…) .

Even if his statement exaggerated the imperial restoration of the old Roman river frontier, the very act of Justinian supervising the Long Walls’ restoration confirms their importance as a key element in Constantinople’s security. Furthermore the events of 559 reveal the empire’s flexible response by forcing the Kutrigurs to withdraw through the threat of the Danube river fleet. New strategies reflecting the transition from a territorial empire to an adaptive state able to selectively apply its resources of manpower and technology. In addition while the Long Walls did not protect all of Constantinople’s water supply, they did secure one major spring from the city’s water supply at Pinarca and the sources of the Hadrianic aqueduct in the Forest of Belgrade1919. Crow et al. 200 (…) . Today the Wall remains like a fairy-tale giant enveloped in a magic forest, hidden but redolent still of great power. It is to be hoped that new research opportunities are able to reveal more of what Edward Gibbon termed Rome’s Last Frontier.

Bardill 2005 = Jonathan Bardill, Brick Stamps of Constantinople, Oxford, OUP, 2005.

Chauvot 1986 = Alain Chauvot, Procope de Gaza, Priscien de Cesarée, Panegyriques de l’empereur Anastase Ier, Bonn, Habelt, 1986.

Crow 1995 = James Crow, “The Long Walls of Thrace”, in Cyril Mango, Gilbert Dagron (eds) Constantinople and Its Hinterland, Cambridge, Society for the Promotion of Byzantine Studies 3, 1995, pp. 118-124.

Crow 2020 = James Crow, “Power and glory: ceremonial gates in Constantinople and the Balkans: prototypes and legacy”, in Emanuele Intagliata, Christophe Courault, Simon Barker (eds), City Walls in Late Antiquity, an empire wide perspective, Oxford, Oxbow, 2020, pp. 65-76.

Crow 2021 = James Crow, “Travels of an exarch: Smaragdus and the Anastasian Walls”, in Thomas J. MacMaster, Nik S. M. Matheou (eds), Italy and the East Roman World in the Medieval Mediterranean: Empire, Cities and Elites, 476-1204, (BBOS 30), Abingdon, Routledge, 2021, pp. 97-108.

Crow, Ricci 1997 = James Crow, Alessandra Ricci, “Investigating the hinterland of Constantinople: interim report on the Anastasian Long Wall”, Journal of Roman Archaeology 10, 1997, pp. 109-124.

Crow et al. 2008 = James Crow, Jonathan Bardill, Richard Bayliss, The Water Supply of Byzantine Constantinople, London, Roman Society Monograph 8, 2008.

Haarer 2006 = Fiona Haarer, Anastasius I, Politics and Empire in the Late Roman World, Leeds, Francis Cairns, 2006.

Hof 2020a = Catherine Hof, Die Stadt Mauer, Resafa 9.1, Berlin, Harrassowitz, 2020.

Hof 2020b = Catherine Hof, “The revivification of the earthen outworks in the late Eastern Empire: the case of Resefa, Syria”, in Emanuele Intagliata, Christophe Courault, Simon Barker (eds), City Walls in late antiquity, an empire-wide perspective, Oxford, Oxbow, 2020, pp. 125-136.

Meyer-Platt, Schneider 1943 = Bruno Meyer-Platt, Alfons-Maria Schneider, Die Landmauer von Konstantinopel, (DAA 8), Berlin, de Gruyter, 1943.

Rizos, Sayer 2017 = Efthymios Rizos, Mustafa H. Sayer, “Urban Dynamics in the Bosphorus Region during Late Antiquity”, in Efthymios Rizos (ed.), New Cities in Late Antiquity, Documents and Archaeology, Turnhout, Bibliothèque de l’Antiquité Tardive 35, 2017, pp. 85-100.

Sarantis 2016 = Alexander Sarantis, Justinian’s Balkan Wars, Campaigning, Diplomacy and Development in Illyricum, Thrace and the Northern World, AD 527-565, Prenton, Francis Cairns, 2016.

Sayer 2021 = Mustafa H. Sayer, “Trakya/Thrace”, in Engin Akyürek, Koray Durak, (eds), Bizans Dönemi’nde Anadolu/Anatolia in the Byzantine Period, Istanbul, Yapi Kredi Yayınları, 2021.

Snyder 2012 = J. Riley, Snyder, Construction requirements of the Water Supply of Constantinople and Anastasian Wall, University of Edinburgh PhD, 2012.

Schneider, Meyer-Platt 1942; Crow 2020.

Rizos, Sayer 2017; Sayer 2021.

Haarer 2006; Hof 2020a.

Procopius of Gaza, p. 21; Chauvot 1986.

Haarer 2006, p. 106-109; Bardill 2005, p. 124, n. 35; Hof 2020a.

Crow, Ricci 1997.

Crow 1995, p. 116-117.

Snyder 2012.

Hof 2020a; 2020b.

Crow, Ricci 1997, p. 239, fig. 2.

Agathias, History, 5, 13, 6.

Crow, Ricci 1997, p. 249, fig. 8.

Snyder 2012.

Snyder 2012, p. 253-255.

Sarantis 2016, p. 161-162.

Sarantis 2016, p. 139-142.

Crow 2021.

De Aed. IV I 33.

Crow et al. 2008.